San Esteban de Gormaz (Soria)

To San Esteban the message arrived

that Minaya was coming for his two cousins

Verses 2845 et seq. CMC

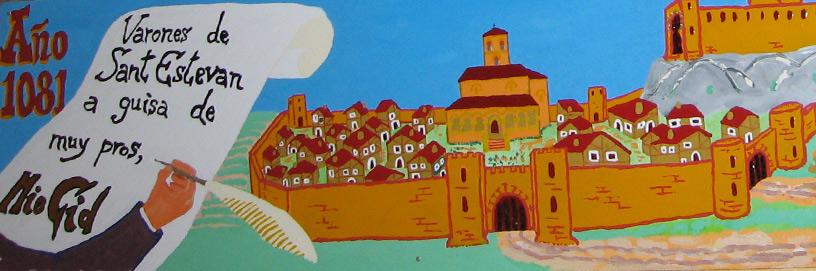

The medieval history of San Esteban de Gormaz, known in the ninth century as "Castro Moro" or "Castro Muros" according to versions, is determined by its geostrategic importance, on the border of the Duero, between Osma and Gormaz. In the year 912, by order of the king of León, the count Gonzalo Fernandez repopulated this area. Since then, and throughout the tenth century until the first half of the eleventh, San Esteban changed from Christian to Muslim hands on several occasions, given its importance as one of the gates of Castile. On September 4, 917, a Muslim army sent by Abderramán III entered Christian territory and sieged San Esteban de Gormaz. This army was defeated by the host of King Ordoño II. The muslim general Ahmad b. Muhammad was killed in battle. According to the Chronicle of Silos after defeating the muslims Ordoño II hung the head of the general in the walls of the castle next to the head of a boar. In retaliation on June 8, 920, the army of Abderramán III entered San Esteban de Gormaz sacked the city and razed it. This is how history was written in the 10th century.

After the death of Almanzor at the beginning of the 11th century and the collapse of the Andalusian caliphate, the weakness of the Taifa kingdoms made possible that, in the middle of the 11th century, under the reign of Ferdinand I, San Esteban would remain in Christian hands. The advance of the borders towards the South moved away the dangers of the war, so San Esteban could develop as a nucleus of importance: in the year 1187 the first Court of Castilla was celebrated there; by then San Esteban had more than 3,000 souls, population figure very similar to the current one.

In the Song of el Cid, San Esteban is quoted repeatedly. This reiteration and the knowledge of the place names of the surroundings, -although sometimes with geographical errors- has led some scholars to think that the anonymous poet could have lived or been a native of this village. The truth is that San Esteban and its surroundings play a very important role in the poem. According to the Song its inhabitants are measured and prudent.

What you can see and do in San Esteban de Gormaz

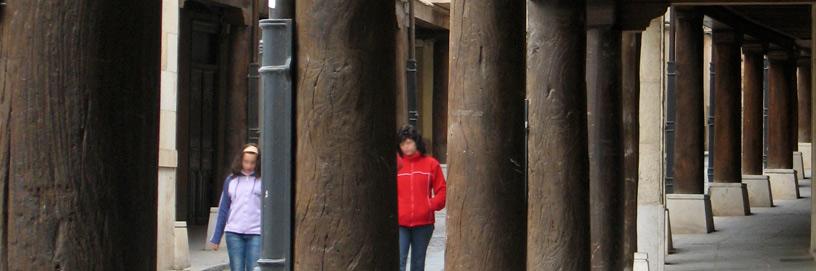

The silhouette of its old castle is the first thing we see as we approach San Esteban de Gormaz although only a few walls and the ruins of the tanks that collected rainwater are all that remains of the 9th century castle, which was first built by the Arabs. Some remains of the old walls can be seen in the town, such as the Town Arch, next to the Douro, the old gate in the outer wall that allowed access to the town and which now leads along a small porticoed street to the Town Hall.

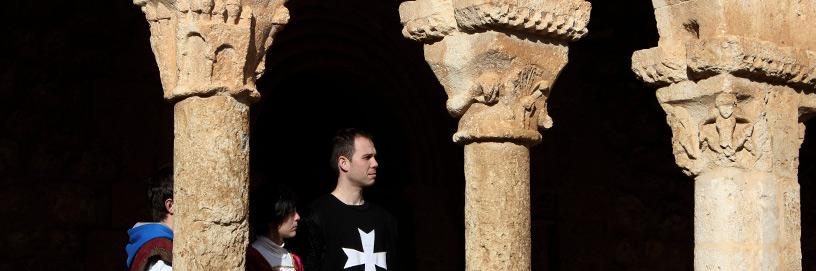

The town’s important Romanesque heritage is seen in the churches of St Michael, which possibly existed when El Cid was banished, and Santa Maria del Rivero. St Michael’s seems to be the older church of the two. One of its stone corbels represents a monk with the text: Iulianus Magister Fecit Era MCXVIIII. Difficulties in reading the date mean that it cannot be determined for certain if the church was finished in 1081 or 1111. If it is the older date, this would be the oldest porched Romanesque church in Spain.

In turn, the church of Santa Maria del Rivero is a large building with a porched gallery and some striking elements inside, such as the Mudejar ceiling of the stairs to the balcony, the curious paintings in the ceiling above the altar, possibly 13th or 14th century, and the Romanesque capitals outside the apse, which are fully covered and therefore in an excellent state of conservation.

A walk around San Esteban inevitably takes us to the River Douro, the reason for this town, and its medieval bridge with 16 arches. Although it has undergone numerous actions in the course of history, it can be imagined that it was very important to possess this safe crossing of the river from the 9th to 11th centuries to strengthen the frontier of the Douro. The bridge is said to have been first built by the Romans. Indeed, if curious visitors look carefully while walking around the streets of San Esteban, they will see some Roman funerary stelae and tiles in the walls of the town houses, where they were used as simple building stones.

Finally, they can visit the Castile and León Romanesque Theme Park, which among other attractions, displays nine big models of the nine most significant Romanesque buildings in the region and a section of the arches of San Juan de Duero, two metres high. San Esteban Ethnographic Museum is next to it and equally open to visits.

You also should not miss

- It is worth sitting down to rest under the porch of either of the two Romanesque churches in San Esteban de Gormaz to breathe in a little history. St Michael’s Church was built in the times of El Cid and you might well be under the oldest church porch in Spain. The sculptures on the capitals and corbels are very interesting but badly worn. If you look carefully, on one of the stones in the balustrade you’ll discover a small board for a game, similar to noughts and crosses: it’s alquerque, a medieval game with an Arab origin. The inhabitants of San Esteban must have used it for generations in the shade that travellers can now share.

Información práctica

- Ayuntamiento: Plaza Mayor, 1 (42330)

- Teléfono: 975 350 002

- Correo electrónico: ayuntamiento@sanesteban.com

- Web: www.sanestebandegormaz.org

- Habitantes: 2376

- Altitud: 859 m.