This section contains complete, updated information about El Cid –the Spanish mediaeval hero par excellence- and his life and times, in addition to information about El Cantar de mío Cid (The Song or The Poem of el Cid) the great Spanish epic poem that tells of the adventures of El Cid from the time of his exile.

On describing the figure of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, el Cid Campeador (the Battler), we must make a clear distinction between documented historical fact and the literary creation of this figure, which is laden with legendary elements and has been adapted to the intrinsic needs of the works that have been written about him. Even today, in modern times, it is quite easy to confuse both planes, the historical and the literary, and although it is necessary to compare them, they must not be confused with each other.

Statue of El Cid, in Burgos.

Statue of El Cid, in Burgos.

Historically speaking, Rodrigo Díaz was a prominent member of the court of Castile during the short reign of Sancho II the Strong (1065-1072) and at the start of the reign of his brother and heir, Alfonso VI, who wed him, more or less in 1074, to one of his relatives, Jimena Díaz. However, an unfortunate accident on the frontier of Toledo led to Rodrigo being exiled in 1081.

From that year until 1086, the Castilian knight, like so many others in his situation, was in the service of a Moorish king, the king of Saragossa in this case, whose territory he defended against his brother, the king of Lérida, who in turn, was an ally of the Count of Barcelona and the King of Aragón.

He defeated them both in the battles of Almenar (1082) and Morella (1084), respectively. After being reconciled with Alfonso VI, Rodrigo returned to Castile in 1086, and was soon sent to the eastern coast to protect the interests of Castile.

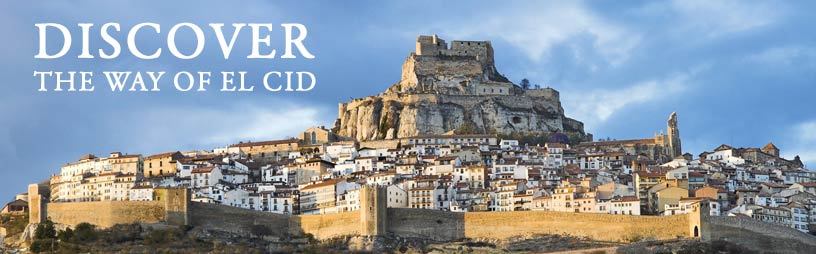

Morella, Castelln.

Morella, Castelln.

After being exiled again by the king in 1089, Rodrigo started to wage war on his own account, and in 1094 he conquered Valencia, where he died in 1099. His mortal remains were taken to the monastery of Cardeña, in Burgos, when the city was evacuated by the Christians in 1102.

This biography serves merely as a backdrop to the legendary creation, and thus, for example, neither the Carmen Campidoctoris (or Latin Poem of El Cid Campeador) nor the Cantar de mío Cid make any allusion whatsoever to the services rendered by El Cid in the kingdom of Saragossa or the battles of Almenar and Morella, whereas in the second case, a fictitious campaign is created in the Jalón valley focused on the taking of Alcocer (a stronghold near Ateca) that served as a bridge for a direct advance towards the south-east, in the direction of Valencia. In this way, the episodes of lightness and darkness in the historical character have been polished to present a shining hero of literature.

Ateca, Zaragoza.

Ateca, Zaragoza.

The contents of this section have been coordinated by Dr. Alberto Montaner Frutos, Professor at Saragossa University and the most important international expert on El Cantar de mío Cid, together with his research team.

REV. ALC: 08.10.18