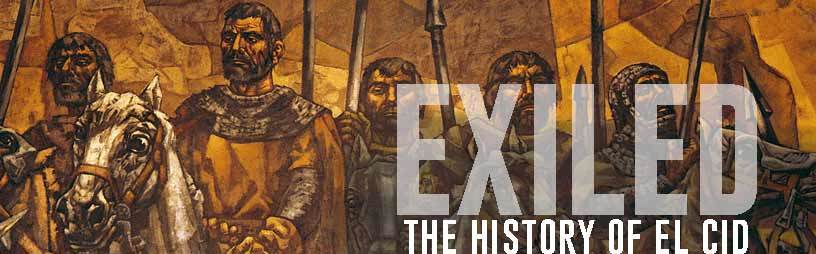

The heroes of epics and ancient and modern songs of deeds are often the result of individual or collective imagination. Some of them, however, are based more or less accurately on people who actually existed, whose fame converted them into legendary figures, to the point that it is very difficult to know which parts of the tale about their deeds have a historical basis. In this, as in many other aspects, the case of El Cid is exceptional.

Although his biography was for many centuries combined with legend, today, quite a good deal is known about his real life and, more amazingly, his autograph actually exists in the form of a signature he affixed in a dedication to the Virgin Mary in Valencia cathedral «in the year of the Incarnation of Our Lord in 1098». In that document, El Cid, who never officially used this designation, presents himself as «Prince Rodrigo the Battler». We shall now learn about his story.

Childhood and youth of Rodrigo: his services to Sancho II

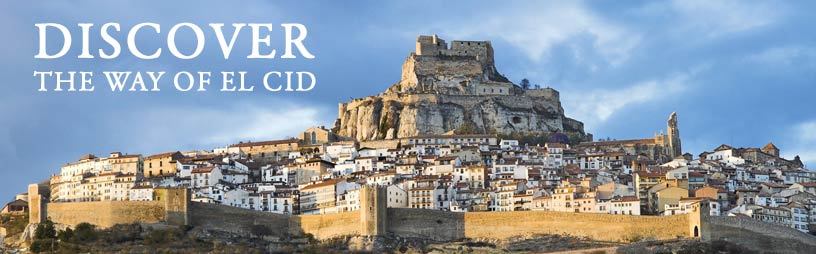

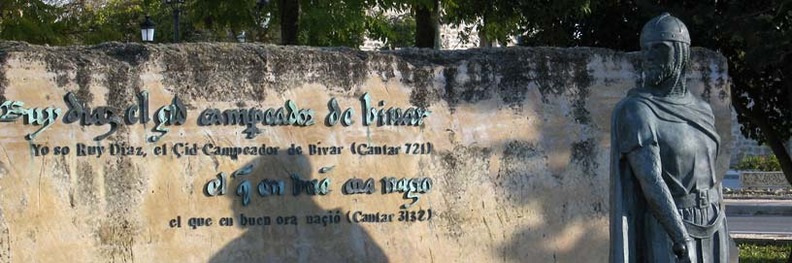

A long-established tradition says that Rodrigo Díaz was born in Vivar (now known as Vivar del Cid), but there is no documentary proof of this. This town belongs to the borough of Quintanilla de Vivar and is located in the Ubierna valley, ten kilometers to the north of Burgos. The date of his birth is not known (this is quite usual among mediaeval characters) and dates have been proposed that range from 1041 to 1057. However, it appears appropriate to determine this date as being sometime between 1045 and 1049.

Vivar del Cid, Burgos

Vivar del Cid, Burgos

Evidence points to his father, Diego Laínez (or Flaínez) being one of the sons of the magnate Flaín Muñoz, who was count of León in approximately 1000. As was the usual case for second sons, Diego left home to seek his fortune elsewhere. In his case, he found it in the Ubierna valley, where he played an important part in the war with Navarre during the year 1054, under the reign of Fernando I of Castile and León. This was when he acquired his estate in Vivar, where Rodrigo was probably born, in addition to seizing the castles of Ubierna, Urbel and La Piedra from Navarre. Despite this, he never frequented the court, perhaps because his family had fallen into disgrace at the beginning of the 11th century, by rising up against Fernando I.

On the other hand, Rodrigo was soon seen in court circles, as he was brought up as a member of the entourage of the dauphin Sancho, the king’s elder son. The king made him a knight and Rodrigo rode alongside him in what would be his first combat, the battle of Graus (near Huesca), in 1063. On that occasion the troops of Castile had decided to help the Morís king of Saragossa, a protégé of the king of Castile, against the advance of the king of Aragón, Ramiro I, who died precisely during that battle.

Upon the death of Fernando I in 1065, he adopted the ancient custom of sharing out his kingdoms among his children, leaving the larger part (Castile) to Sancho; Alfonso was given León and García, Galicia. He also made each of them the protector of two Andalusi kingdoms, which were to pay them a peerage (a tax in return for their protection). The balance of forces remained unstable and conflicts soon began to break out, which finally led to war.

View of Burgos.

View of Burgos.

In 1068 Sancho II and Alfonso VI confronted each other in the battle of Llantada, on the banks of the river Pisuerga, where the former defeated the latter, although the battle was not decisive. In 1071, Alfonso managed to control Galicia, which was divided between him and Sancho, but this failed to put an end to the conflicts, and in 1072 the battle of Golpejera or Vulpejera was waged, near Carrión, in which Sancho defeated Alfonso and took him prisoner, in addition to taking over his kingdom.

Young Rodrigo (who would at that time have been about 23 years old) stood out as a brave knight during these confrontations and, according to an old tradition, documented at the end of the 12th century, he became second lieutenant or standard bearer of Sancho during those combats, although the documents written at that time contain no record of his holding that post. On the contrary, it is likely that he earned the name of “Campeador” (or “Battler”) at that time, which would accompany him for the rest of his life, to the point of being referred to by both Christians and Muslims as “Rodrigo el Campeador”.

Following the defeat of Alfonso (which led him to be exiled in Toledo), Sancho II had reunified the territories ruled by his father. However, he was not able to enjoy this new situation for long. At the end of the same year, 1072, a group of nobles from León, who were not content with things, decided to support the dauphine, Urraca, sister of the king, and rose up against him in Zamora. Sancho laid siege to Zamora with his army, during which Rodrigo also performed heroic deeds, but the king paid with his life, and was struck down during a bold plot devised by the knight from Zamora, Bellido Dolfos.

El Cid in the service of Alfonso VI and the reasons for his exile

The unexpected death of Sancho II paved the way for his brother, Alfonso, to claim the throne. He quickly returned from Toledo to occupy his place. The 13th-century legend shows the famous image of a solemn Rodrigo who, speaking out for the distrustful vassals of Sancho, obliged Alfonso to swear he had nothing to do with the death of his brother Sancho in the church of Santa Gadea (or Agatha) in Burgos, which would have earned him the enmity of the new monarch.

On the contrary, no-one requested him to take that oath, and in addition the Battler, who was a regular member of court, had earned the trust of Alfonso VI, who appointed him judge in a series of quarrels with Asturias in 1075.

Hermitage of Santa Cecilia, Santibez del Val - Barriosuso, Burgos

Hermitage of Santa Cecilia, Santibez del Val - Barriosuso, Burgos

Furthermore, at approximately the same time (most probably 1074), the king married him to one of his relatives, his third cousin Jimena Díaz, a noblewoman from León who, according to recent research on the subject, was also second niece of Rodrigo himself on his father’s side. This marriage was the kind of marriage that a nobleman of first rank would aspire to achieving, which just goes to show that the Battler was very well situated in court circles.

This is also shown by the fact that Alfonso placed him at the head of the group of ambassadors he dispatched to Seville in 1079 to collect the peerages owed by king Almutamid, while García Ordóñez (one of the guarantors of the marriage agreements made by Rodrigo and Jimena) went to Granada on a similar mission. While Rodrigo was performing his task, the king Abdalá de Granada, supported by the Castilian ambassadors, attacked the king of Seville. As the king was a protégé of Alfonso VI, precisely due to the fact of paying the peerages the Battler had gone to collect, the latter was forced to defend the Almutamid and defeated the invaders in Cabra (in what is now the province of Córdoba), and captured García Ordóñez and other Castilian magnates.

The traditional version is that the fact that Rodrigo had defeated one of his own was not well considered in high court circles, for which reason people began to speak ill of him to the king. However, there is no proof that this caused any hostility against the Battler, among other things, because Alfonso VI was interested in supporting the king of Seville against the king of Badajoz, for political reasons, and so he was likely not at all pleased by the participation of his nobles in the attack by Granada.

Santo Domingo de Silos, Burgos

Santo Domingo de Silos, Burgos

In all cases, similar political reasons led Rodrigo to fall into disgrace. During that difficult time, Alfonso VI maintained king Alqadir (who was merely a puppet) on the throne of Toledo, despite the opposition of many of his subjects. In 1080, while the Castilian king was leading a military campaign to restore the government of this protégé, an uncontrolled Andalusi faction from the north of Toledo attacked Gormaz (province of Soria).

Rodrigo stood up to the invaders and routed them with his small army, driving them outside the frontier, which, in principle, was merely a routine operation. However, under those circumstances the Castilian attack would serve as an excuse for the faction opposing Alqadir and Alfonso VI. In addition, the other chieftains began to ask themselves why they were paying taxes if it did not guarantee them protection. Consequently, apart from García Ordoñez or other noblemen (the count of Nájera) who were against Rodrigo intervening in the matter, the king had to take a wise decision in this respect, in keeping with the customs of the times. So he forced the Battler into exile.

Gormaz, Soria.

Gormaz, Soria.

The first of the exiles of El Cid and the services he rendered to the kingdom of Saragossa

Rodrigo Díaz was most likely exiled at the beginning of 1081. Like many other knights before him who had lost the king’s favour, he went in search of a new lord who he could serve, together with his small army. Apparently he went first to Barcelona, where two brothers were ruling at that time, Ramón Berenguer II and Berenguer Ramón II, but they did not consider it a good idea to take him into their court. In the face of this rejection, the Battler might have sought the support of Sancho Ramírez de Aragón.

It is not known why he did not do this, but we should not forget that Rodrigo had taken part in the battle in which the father of the king of Aragón had died. Be that as it may, the case is that Rodrigo decided to go to Saragossa and serve its king. It was not unusual for a Christian knight to act in this way, since Muslim courts were often, for one reason or another, a shelter for noblemen from the north. We have already seen how Alfonso himself had found protection in the city of Toledo.

When Rodrigo reached Saragossa, the aged king Almuqtadir was still ruling. This same king had ruled during the times of the battle of Graus. He was one of the most brilliant monarchs of the small kingdoms and a famous warrior and poet, who had built the palace of la Aljafería. But the old king died shortly afterwards, and his kingdom was divided between his two sons, Almutamán, king of Saragossa and Almundir, king of Lérida.

The Battler continued to remain in the service of Almutamán and helped him defend his frontiers against the advance of the Aragonese in the north and the pressure exerted by Lérida in the east. The most important battles fought by Rodrigo during this period were that of Almenar in 1082 and Morella in 1084. The first of these took place just after Almutamán ascended to power. The town, not wishing to pay tribute to the elder brother, had reached an agreement with the king of Aragón and the count of Barcelona to obtain their support.

Morella, Castelln.

Morella, Castelln.

Fearing an imminent attack, the king of Saragossa sent Rodrigo to guard the north-eastern frontier of his kingdom, the one nearest Lérida. So at the end of the summer or beginning of autumn of the year 1082, the Battler went to inspect Monzón, Tamarite and Almenar, close to Lérida. Meanwhile, he seized the castle of Escarp from Lérida, located at the point where the rivers Cinca and Segre merge, Almundir and the count of Berenguer de Barcelona laid siege to Almenar castle, which forced Rodrigo to return in haste.

After fruitless negotiations with the attackers to try and get them to lift the siege, Rodrigo attacked them and, despite the fact that his followers were few in number, he defeated them and captured the count of Barcelona. The battle of Morella in 1084 occurred in a similar way. After sacking the lands to the south-east of the kingdom of Lérida, and attacking the impressive stronghold of Morella, the Battler fortified the castle of Olocau del Rey, to the north-east of Morella. Almundir, faced with the possibility of the garrison of Saragossa being so near, decided to attack them, in the company of Sancho Ramírez de Aragón. The clash took place near Olocau (most likely on 14 August 1084) and during the battle, after heavy fighting, Rodrigo again emerged victorious, and captured the most important magnates of Aragón.

Olocau del Rey, Castelln.

Olocau del Rey, Castelln.

The reconciliation with king Alfonso VI and the battles waged on the eastern seaboard

Almutamán died in 1085, probably in the autumn of that year, and was succeeded by his son Almustaín, who the Battler served, but not for long. In 1086, Alfonso VI, who had finally conquered Toledo the year before, laid siege to Saragossa with the firm resolution of taking it.

However on 30 July, the emperor of Morocco disembarked with his troops, the Almoravids, ready to help the Andalusi kings drive back the Christians. The king of Castile had to lift the siege and go to Toledo to prepare a counter attack, which ended in the great defeat of Sagrajas inflicted by the Castilian troops on 23 October of that year. Rodrigo then regained the king’s favour and returned to Castile.

It is not known whether the reconciliation took place during the siege of Saragossa or shortly afterwards, but no record exists that it took place during the battle of Sagrajas. Apparently, he was entrusted with guarding several strongholds in what are now the provinces of Burgos and Palencia. At any rate, Alfonso did not use the services of the Battler on the southern flank, but, taking advantage of his experience, he sent him to the eastern part of the Peninsula.

After remaining in court until the summer of 1087, Rodrigo left for Valencia to help Alqadir, the deposed king of Toledo whom Alfonso VI had compensated for his loss, by making him head of the kingdom of Valencia, where he found himself in the same weak position as he has suffered in Toledo.

Ayub castle. Calatayud, Zaragoza.

Ayub castle. Calatayud, Zaragoza.

The Battler went first to Saragossa, where he met with his former master Almustaín and together, they set out for Valencia, which was under siege by the archenemy of both, Almundir of Lérida.

After routing the king of Lérida and assuring Alqadir the protection of Alfonso VI, Rodrigo remained alert, while Almundir occupied the stronghold of Murviedro (i.e., Sagunto), again threatening Valencia. The tension increased and the Battler returned to Castile, where he remained during the spring of 1088, most likely in order to explain the situation to Alfonso and plan future action. Such action consisted of an intervention in Valencia on a huge scale, with Rodrigo leaving for the front with a large army, in the direction of Murviedro.

Sagunto, Valencia.

Sagunto, Valencia.

Meanwhile, the circumstances in that area had changes for the worse. Almustaín, to whom the Battler had refused to surrender Valencia the previous year, had now formed an alliance with the count of Barcelona, and this forced Rodrigo in turn to seek an alliance with Almundir. The paths of the old friends separated and the former enemies forged an alliance. In these circumstances, when Rodrigo reached Murviedro, he found that Valencia was surrounded by the troops of Berenguer Ramón II.

The confrontation seemed imminent but this time, diplomacy proved to be more effective than weapons, and following a series of negotiations, the count of Barcelona withdrew without a fight. Then Rodrigo acted in a very strange way for a royal envoy, and started to collect the taxes that were formerly paid to the Catalan counts or the king of Castile for himself, in Valencia and the other territories of the eastern seaboard. This attitude suggests that during his time at court, Alfonso VI and Rodrigo has reached an agreement to achieve the true independence of the Battler, in return for defending the strategic interests of Castile on the eastern flank of the Peninsula. This situation, in fact, would become a reality at the end of 1088, following the sinister incident of the castle of Aledo.

The second exile; El Cid, the warlord

It happened that Alfonso VI had managed to control this stronghold (in what is now the province of Murcia), which was threatened by the small kingdoms of Murcia, Granada and Seville, against which the Castilian troops posted there launched continuous attacks.

Bocairent, Valencia.

Bocairent, Valencia.

This situation, in addition to the activity of the Battler in the east, moved the kings of these kingdoms to once more ask for the support of the emperor of Morocco, Yusuf ben Tashufin, who disembarked with his forces in the early summer of the year 1088 and laid siege to Aledo. As soon as Alfonso found out about this situation, he left to help the besieged stronghold, and sent instructions to Rodrigo to meet him.

The Battler marched towards the south, where he approached the region of Aledo, but he failed to meet the troops from Castile as he had promised. It is not certain whether this was just an error in coordination during a time when communications were difficult to establish, or deliberate disobedience on the part of the knight from Burgos, who had other plans. This will never been known, but the result was that Alfonso VI considered the action of his vassal to be unforgivable and again condemned him to exile, and even expropriated his property, which was only usually done in cases of treason. From this time on, the Battler became an independent leader and continued to act in the eastern region of the Peninsula guided only by his own interests.

Elche, Alicante.

Elche, Alicante.

He started to act in the region of Denia, which at that time belonged to the kingdom of Lérida, and this led to Almundir sending an ambassador to negotiate peace with Rodrigo.

After signing the peace treaty, Rodrigo returned to Valencia in 1089, where again he was able to collect the taxes of the capital and those of the main strongholds of that region. Then he headed towards the north and in the spring of 1092, he reached Morella (which is in what is now the province of Castellón). Almundir, to whom that region belonged, was afraid that the treaty might be broken and again forged an alliance against Rodrigo with the count of Barcelona, whose troops marched southward, in search of Rodrigo.

The clash took place in Tévar, to the north of Morella (perhaps the site of the pass of Torre Miró) and there, Rodrigo inflicted the second defeat on the allied troops of Lérida and Barcelona, and again captured Berenguer Ramón II. This victory firmly consolidated the dominant position of the Battler in the east, as before the end of the year, probably in the autumn of 1090, the count of Barcelona and the Castilian leader sealed a pact by which the former would stop intervening in the area and leave Rodrigo free to act in the future.

Beach in Cullera, Valencia.

Beach in Cullera, Valencia.

In principle, the Battler limited himself to collecting taxes in Valencia and to controlling some strategic strongholds that allowed him to dominate the whole territory, i.e., to maintain the type of protectorate he had been exercising since 1087. With this purpose, in 1092 Rodrigo rebuilt the castle of Peña Cadiella (today, La Carbonera, in the mountains of Benicadell), where he established his operations base. Meanwhile, with the intention of recovering the initiative in the east, Alfonso VI established an alliance with the king of Aragón, the count of Barcelona and the cities of Pisa and Genoa, whose respective troops and fleets took part in the expedition, and marched on Tortosa (at that time, this city paid taxes to Rodrigo) and the city of Valencia, during the summer of 1092.

This ambitious plan failed, however, and Alfonso VI was forced to retreat to Castile just after reaching Valencia, without having obtained any benefits from the campaign. Rodrigo, on the other hand, who was then in Saragossa, negotiated an alliance with the king of that city and launched an attack in reprisal against La Rioja.

From then on, only the Almoravids were able to stand up to the domain of the Battler in the eastern seaboard. It was then that Rodrigo finally decided to change from a policy of establishing protectorates to one of conquest. In actual fact, at this time the third and final arrival of the Almoravids in Al-andalús, in June 1090, had radically changed the situation and it was clear that the only way to regain control over the east and overcome the power of the Moors was to occupy the main strongholds of this area.

The conquest of Valencia

While Rodrigo continued to remain in Saragossa and until the autumn of 1092, Valencia was the scene of an uprising led by the Cadí (judge) Ben Yahhaf after overthrowing Alqadir, who was murdered, favouring the advance of the Almoravids. The Battler, however, returned to the east and his first step was to siege the castle of Cebolla (now el El Puig, near Valencia) in November 1092.

Following the surrender of this stronghold in 1093, Rodrigo now had a foothold in the capital, which was finally laid to siege in July of that year. This first assault lasted for the whole of August and was lifted on condition that the Moors who had come to Valencia after the rebellion that had cost the life of Agadir, withdrew from the city. However, at the end of the year, the siege had again been estalished and would not be lifted until the city fell. Then, at the request of the people of Valencia, the Almoravids sent an army commanded by prince Abu Bakr ben Ibrahim Allatmuní, which got as far as Almussafes (about 20 kilometres to the south of Valencia) and eventually withdrew without putting up a fight. Now that there was no further external support, the situation became unbearable and Valencia finally surrendered to Rodrigo on June 15 1094. From then on, Rodrigo adopted the name «Prince Rodrigo the Battler» and most certainly received the Arab title of Sídi «my lord», the origin of his assumed name, mio Cid or el Cid, by which he was subsequently known by all.

Valencia

Valencia

The conquest of Valencia was a resounding triumph, but the situation was far from safe. On the one hand, the Almoravids continued to apply pressure, and this situation continued for as long as the city remained in the power of the Christians. On the other hand, obtaining control over the territory made it necessary to conquer new strongholds.

The reaction of the Moors was not long in coming and in October 1094 an arm commanded by the general Abu Abdalá marched on the city. It was defeated by El Cid in Cuart (now Quart de Poblet, just six kilometres to the western part of north-east Valencia). This victory gave the Battler a respite and he was able to obtain new victories during the following years, so that by 1095 the site of Olocau was won, in addition to the castle of Serra. At the beginning of 1097 the last expedition of the Almoravids during the lifetime of Rodrigo took place, under the command of Muhammad ben Tashufin.

Castle of Corbera, Valencia.

Castle of Corbera, Valencia.

This ended with the battle of Bairén (about five kilometres to the north of Gandia), and once again, Rodrigo was victorious, this time with the help of the troops of King Pedro I of Aragón, with whom Rodrigo had forged an alliance in 1094. This victory allowed him to continue his conquests so that finally, at the end of 1097 the Battler won Almenara and on 24 June 1098 he succeeded in occupying the powerful stronghold of Murviedro, which considerably strengthened his domain of the eastern seaboard.

This was his last conquest, for just one year later, possibly in May 1099, El Cid died in Valencia of natural causes, at the age of less than fifty-five years (a normal age during a time when life expectancy was very low).

San Pedro de Cardea, Burgos

San Pedro de Cardea, Burgos

Although the situation of the Christian occupants was quite complex, they managed to resist for two more years, under the rule of Jimena, until the advance of the Almoravids was impossible to halt. At the beginning of May, 1102, with the help of Alfonso VI, the family of El Cid and his followers abandoned the city, taking with them his mortal remains, which were buried in the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña, in Burgos.

San Pedro de Cardea, Burgos

San Pedro de Cardea, Burgos

Thus ended the life of one of the most famous characters of his time, but by then the legend had commenced.

Author: Alberto Montaner Frutos, Professor at the University of Saragossa, Spain.

Rev. ALC: 06.02.19